While there’s a growing political argument on the right that children must be protected from “indoctrination” by the government in schools, there is also news this week about the very real need for the government to protect children from exploitation, such as in a series of scary stories about child labor.

The two issues aren’t related, but they both speak to the involvement of government in the lives of US kids.

Protecting children from ‘indoctrination’

The conversation about protecting kids from so-called indoctrination has mostly played out in recent years in terms of Covid-19 restrictions that angered many parents and school curriculums that make some uncomfortable.

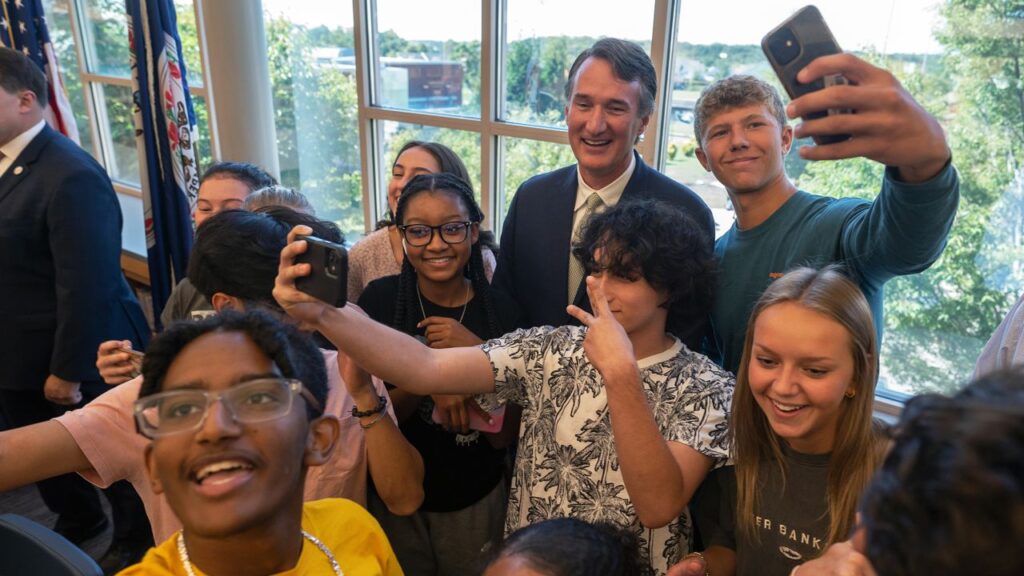

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin rode a message of “parental rights” to victory in a battleground state in 2021, which has made him a much-discussed potential contender for the 2024 Republican presidential primary.

He’s one of a number of Republican governors who are focused on cleansing schools of history lessons about race that they find objectionable and making schools less accommodating of transgender students, although he was unable to get all of his proposals passed into law.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, another potential Republican presidential candidate, has a GOP-controlled legislature willing to do his bidding and has turned himself into a lightning rod by actively opposing what he says is “woke indoctrination” in schools.

At a news conference in Florida on Wednesday, he argued his administration is not banning certain books with graphic content, but rather helping parents to root them out of school districts. After playing a video showing examples of books with graphic illustrations he said were found in some school districts, DeSantis rejected the argument that restricting books in schools is tantamount to banning them.

“It’s a hoax in service of trying to pollute and sexualize our children,” he said.

He also defended state laws he signed that restrict how teachers can address issues of systemic racism.

“It’s wrong to just identify somebody who is a young kid going to school and saying they’re guilty of things they had nothing to do with,” DeSantis said.

We’ve written here before about a proposed curriculum for an Advanced Placement course on African American studies. At the news conference, DeSantis said what he was opposed to in the course was the inclusion of references to queerness in the class and what he perceived as “neo-Marxism.”

Youngkin has also waded into these issues. He backed requiring schools to inform parents of their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity and set up a tip line for parents to report on so-called “divisive” concepts, although a CNN review of complaints to the line showed it did not get much use for that purpose.

A plan put forward by his state’s education department to dramatically edit history and social science standards was changed after it drew criticism for failing to mention Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Juneteenth – the two federal holidays directly related to Black history, racial equality and civil rights.

The Florida example

In Florida, DeSantis’ efforts to restrict what’s in schools in the aim of avoiding graphic content and what he views as indoctrination has led to compelling reports that teachers are increasingly careful about what they can say – and erring on the side of saying little at all, as The Washington Post notes.

These questions about US education will continue as the classroom becomes increasingly political and the country becomes increasingly diverse. DeSantis has pledged to end all diversity programs in state colleges, by the way.

Diversity can’t be stopped

Soon, every race and ethnicity will be a minority. The country is changing and diversifying and a growing majority of Americans under 18 are non-White, according to census data. See it here.

In fall 2009, 54% of US public school students were classified as White, per the Department of Education. In fall 2020, that figure was 46%. And by fall 2030, it will be 43%. The percentage of Asian, Hispanic and multiracial students is growing. The percentage of Black students is shrinking.

Government also needs to protect children

Separate from education issues, a raft of scary stories about teenagers forced into physically demanding and dangerous jobs rather than school has touched off a new pledge by the Biden administration to crack down – and brought the reality of child labor into the headlines.

The New York Times looked at immigrant teenagers hoping to find work as day laborers and in food-production facilities.

The Washington Post found a 13-year-old employed by a cleaning company at a Nebraska slaughterhouse.

Reuters reported on fines imposed by the Labor Department on a major food safety sanitation company for employing teenagers in dangerous jobs at meatpacking plants in multiple states.

From that report:

The department said Packers Sanitation Services Inc allowed at least 102 children between 13 and 17 years old to work overnight shifts and use hazardous chemicals to clean dangerous meat processing equipment such as brisket saws and “head splitters” used to kill animals.

These glimpses of the reality of kids found working in meat plants comes at an awkward moment for the movement in several states to loosen some child labor laws – such as in Arkansas, where Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a measure to no longer require employers to obtain work certificates for children under 16. The paperwork was considered onerous.

“The Governor believes protecting kids is most important, but this permit was an arbitrary burden on parents to get permission from the government for their child to get a job,” Sanders’ spokesperson Alexa Henning said in a statement. “All child labor laws that actually protect children still apply and we expect businesses to comply just as they are required to do now.”

The issue of child labor is obviously distinct from school curriculums, but they both feed into the larger question over how involved government should be in the lives of American young people.